When Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote his landmark essay “Nature” in the 1830s he lived in a world in which it was still possible to isolate oneself from civilization and technology and other people entirely and be alone with one’s soul in the wilderness. There were still parts of the country which no man had yet laid claim to. But now things are different, and there is, at least in Florida, very few pieces of property to which no one holds the deed, and very few swaths of untouched land which have not been targeted by corporations for demolition and the subsequent erection of buildings and shopping malls thereupon. In addition to the proliferation of civilized, resource-expending man, there is also a widespread psychological shift from Emerson’s time, which always accords with the development of new technologies, especially communicative technologies: there is a compulsive need to guzzle up relevant information about the positions of our fellows (viz. social networking, Foursquare, cellular phones). The idea of venturing, even into civilization, without three or more means of contacting our fellow-man (excluding our mouths!) is unthinkable. Why is this? Has our world gotten any more dangerous since the times of transcendentalist yore? No, if anything it has gotten less dangerous because we have sterilized the natural Way (which is, as some see it, an unforgiving Way) of our surroundings. Have our bodies gotten softer from then to now? That is certainly possible, but we did it to ourselves.

I know I am not the first of my generation to spout these sentiments, but I wish to examine the problems of according with nature in our modern world. Is it even possible to be a Luddite, to abhor technology? How far can one possibly go without encountering civilization? Perhaps, as I wish to posit, the answer for the twenty-first century is not to cast off all our technological restraints sheerly for the purpose of making a statement or deviating from the cultural current (though we should not be ‘checking in’ to the forest or the pond) but to first and foremost, leave the barriers of the road and experience Nature before we make any presumptions about it. The important thing for modern man is not that he cuts all ties to progressive civilization but that he reestablishes ties with the great mother beneath this progressive civilization, the great mother whose beauty spans and is the globe. Then, if we wish, we can leave behind our phones and our families and be alone as Thoreau was. But not until we are well-acquainted with the real fibre and fabric of life, the suchness of the ground beneath us.

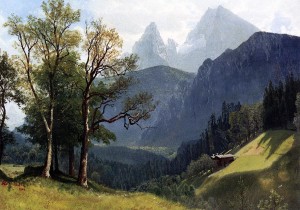

As a culture we seem to be obsessed with what Zen master Shunryu Suzuki would call a “gaining idea”; the intention to get some benefit or possession from doing something. It is difficult to find anyone who does something “just to do it” anymore. There is nothing to be gained from climbing a tree, besides a slightly better view of our surroundings, but it is good to do it anyway, because when we climb a tree we, as a young civilization being nurtured by a great mother, come as close as we can come to suckling on this great mother’s breast. It is not enough to look at nature through a photograph and appreciate the lines of the mountain and the sparkle of the river. One must touch and grapple with nature the way one grapples with a dog, letting it lick one’s hand and sniff one’s feet. One must get comfortable with nature, and the only way to do this is by dropping our fears and feeling the bark beneath our fingers. The bark sinks into the untrained hand while the arms pull the body up into the branches. What is to be gained from this? No revelation of height, no treetop epiphany, just the joy of doing without frills or ostentation. The walk through the open field is only half about the sunny beauty of the field … it is also about the steps one takes, each step. Nature is the best teacher of one of the most important facts of life: it is the journey, and not the destination, that counts. In this way, uncivilized nature in its very essence differs from roads and houses and office buildings.

It is contact with this nature of which I am speaking that counts, especially for our deluded and disillusioned present society. We always hear about texting while driving or people who have been run over because they were listening to music while crossing the street. These facts are symptomatic of a fear most seem to have of undiluted atmosphere and nature … is it so hard to walk the city street and listen to the buzz of the people? Is it so hard to drive down the country road without texting a friend for company? I believe that these tendencies come from a core unwillingness to face the hard facts of nature. This fear has spawned a generation’s worth of self-indulgence, and the more self-indulgent and self-gratifying we become, the less we are capable of exploring and experiencing an uncompromising, uncontrollable entity such as Nature is. If one wants to climb the tree, one must simply climb it. If one wants to cross the stream, one must cross it. Of course we may build bridges and cut down trees to make roads, because this is the result of the human will, but it is a sin to lose respect for the river over which the bridge was built. The human body contains no plastic and no mortar, it only contains water and cells, the same cells which grow in the grass underneath our feet. We have an affinity with Mother Nature which it is insanity to deny, and the more ignorant of this fact we become, the more doomed our future is. These are all things you have surely heard before, but I wish to affirm to you that communing with nature has more than just an aesthetic benefit: Nature silently teaches a greater lesson than all the world’s pedagogues, and this lesson can only be learned by contacting Nature through a humble exercise of will, by challenging Nature and giving our egos up to it.

So do not attempt to replicate Thoreau, do not attempt to immediately cast off all your cellular devices and your social networks and venture into the wilderness, because what is wrong and adored is not as important as what is right and abhorred. By this I mean that before we become neo-transcendentalists, Luddites attempting to slash off the social parts of our being, we should understand what Thoreau witnessed when he held the butterfly in his hands or sniffed the plant. He saw what a great many of us appear to be missing. Nature, without a word, teaches us to do, to do for the sake of doing and to grow high like the wild pine. So lose the fears you have been conditioned into, the fears of wild animals and scrapes and bruises, and venture out to discover your true home, the source of your truest strength, the home that, as Faulkner says, is no man’s but all men’s.